Willie Dunn: In Memory of the Legendary Mi’kmaq Filmmaker | Curator’s Perspective

Willie Dunn: In Memory of the Legendary Mi’kmaq Filmmaker | Curator’s Perspective

Filmmaker and folk singer William Lawrence “Willie” Dunn (1941–2013) was one of the first Indigenous directors in the world.[i] To commemorate the 10th anniversary of Willie Dunn’s passing, this instalment of Curator’s Perspective explores and showcases the NFB filmography of this acclaimed Mi’kmaq artist.

To begin with, I invite you to revisit Dunn’s first film, The Ballad of Crowfoot (1968), often referred to as Canada’s first modern music video. This 10-minute short is a collage of archival photographs, put together in a rhythmic montage, similar to what the great Santiago Álvarez was doing at the time in Cuba in films like Now (1965) and L.B.J. (1968). “The Ballad of Crowfoot is a powerful look at colonial betrayals… [with] a ballad composed by Dunn himself about the legendary 19th-century Siksika (Blackfoot) chief who negotiated Treaty 7 on behalf of the Blackfoot Confederacy.”[ii]

The Ballad of Crowfoot, Willie Dunn, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Willie Dunn as Film Director: The Indian Film Crew

The first, historic all-Indigenous production unit, the Indian Film Crew as it was then known, was formed at the NFB’s Montreal headquarters in 1968 as part of the Challenge for Change program. NFB executive producer George Stoney explained the impetus behind the initiative in a letter written in 1972: “There was a strong feeling among the filmmakers at the NFB that the Board had been making too many films ‘about’ the Indian, all from the white man’s viewpoint. What would be the difference if Indians started making films themselves?”[iii]

The great Willie Dunn (Mi’kmaq, raised in Montreal) was part of the first cohort of the Indian Film Crew (active until 1971), which also included six other groundbreaking Indigenous filmmakers from Indigenous communities across Canada: Roy Daniels (Anishinaabe, from Manitoba); Morris Isaac (Mi’kmaq, from Restigouche, New Brunswick); Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell (Kanien’kehá:ka/Mohawk, from Akwesasne, Ontario); Tom O’Connor (Anishinaabe, from Manitoulin Island, Ontario); Noel Starblanket (Cree, from the Star Blanket First Nation, Saskatchewan); and Barbara Wilson (Haida, from Haida Gwaii, BC).[iv] These filmmakers are credited as directors or co-directors on seven NFB films in total, including Crowfoot:[v] Loon Lake (1968); Travelling College (1968); You Are on Indian Land (1969, Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell); These Are My People… (1969, Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell, Willie Dunn, Barbara Wilson and Roy Daniels); The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson’s Bay Company (1972, Martin Defalco and Willie Dunn); and Who Were the Ones? (1972, Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell).

You Are on Indian Land, Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

The Other Side of the Ledger, co-directed by Dunn and Martin Defalco, takes a look at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s 300th anniversary in 1970, offering “an Indigenous perspective on the company, whose fur-trading empire drove colonization across vast tracts of land in central, western and northern Canada. There is a sharp contrast between the official celebrations… and what Indigenous people have to say about their lot in the Company’s operations.”[vi] The Other Side of the Ledger could be compared to contemporaneous films directed by acclaimed Bolivian director Jorge Sanjinés, such as El coraje del pueblo [The Courage of the People] (1971) and El enemigo princial [The Principal Enemy] (1974), which also captured the contrasts between an Indigenous narrative and the “official” one in their exploration of South America’s colonization of lands and Indigenous nations. The Other Side of the Ledger is considered by critics, filmmakers and scholars to be an essential NFB title.

The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Martin Defalco & Willie Dunn, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Willie Dunn as Music Composer: Five Films at the NFB

By the early seventies, Dunn gained world recognition as an accomplished musician, recording self-titled albums that included beloved songs like “I Pity the Country” (1971) and, of course, “The Ballad of Crowfoot” (1972). Dunn’s songs can arguably be considered classics today, the equivalent of what Willie Dixon’s “Hoochie Coochie Man” (1954) meant for Black American popular music or what Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” (1965) meant for American folk rock.

While recording his albums, Dunn started working with Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell on another film: Who Were the Ones? Like The Ballad of Crowfoot, this is an NFB landmark that blends images and a song by Dunn (sung by Bob Charlie), edited rhythmically “to expresses the bitter memories of the past, of trust repaid by treachery, and of friendship debased by exploitation upon the arrival of European colonists.”[vii]

Who Were the Ones?, Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Between 1971 and 1984, Dunn’s music was used in four other NFB films: Paper Boy (1971) by Clay Borris, Cold Journey (1975) by Martin Defalco, Rose’s House (1977) by Clay Borris and Incident at Restigouche (1984) by Alanis Obomsawin. The last title is about the fishing restrictions in a Mi’kmaq community and features Dunn’s “The Salmon Song,” the only recording of which exists in this film (at the 3:33 mark). “Released in 1984, Incident at Restigouche portraits the groundbreaking and impassioned account of the police raids brought by Alanis Obomsawin to international attention. The film features a remarkable on-camera exchange between Obomsawin herself and provincial Minister of Fisheries Lucien Lessard, the man who’d ordered the raid.”[viii]

Incident at Restigouche , Alanis Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Willie Dunn as Performer: Immortalized in Two Films

Dunn also performs his music in two NFB films. In The Other Side of the Ledger (featured above), he has an immortal cameo singing “I Pity the Country,” probably his most famous song. Dunn only appears on camera briefly at the end of the film (38:45–39:00), but he and Defalco decided to create another striking montage of his decolonial music, juxtaposing images of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s 300th anniversary, pictures of European colonizers and land exploitation, and shots of fans at one of Dunn’s concerts.

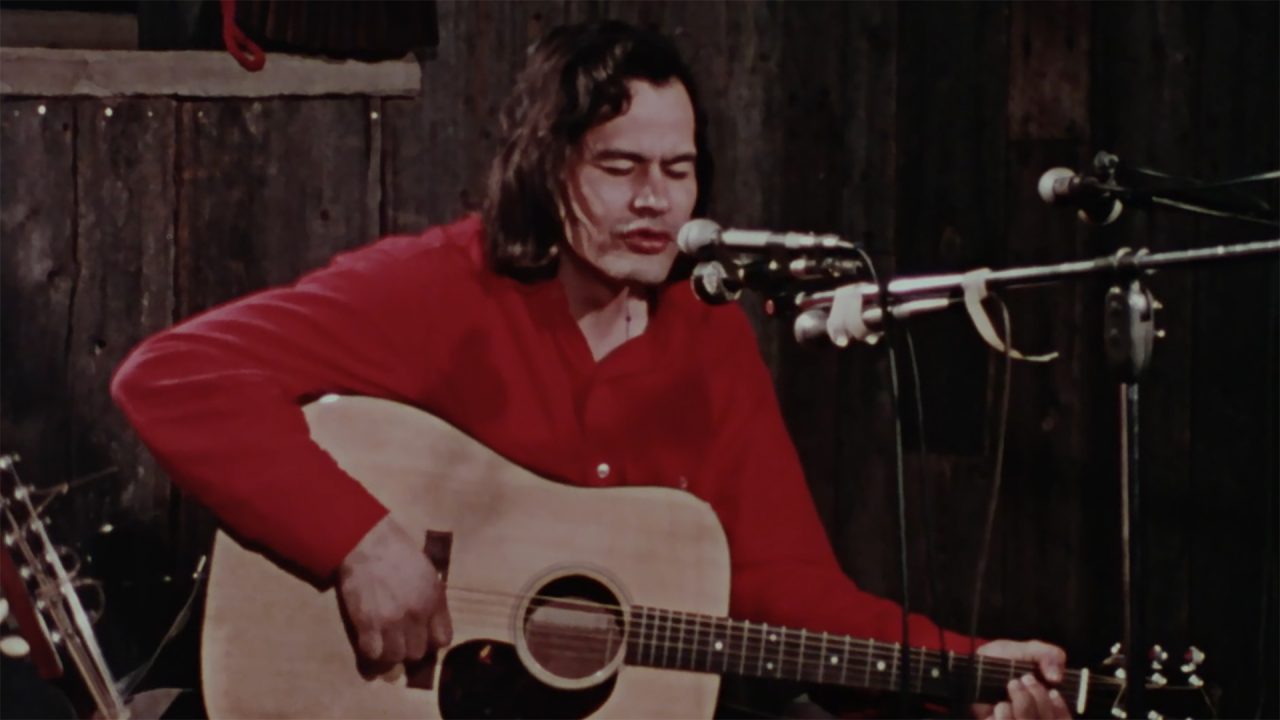

But the best NFB depiction of Dunn performing can be found in Alanis Obomsawin’s Amisk (1977). “In 1977, the James Bay Festival took place over nine days in Montreal. This historic one-of-a-kind event was held in support of the James Bay Cree whose territory, resources and culture were threatened by the expansion of hydro-electric dams. First Nations, Métis and Inuit performers came from across North America to show their support in an act of Indigenous unity and solidarity few people in Montreal had ever witnessed.”[ix] Right after the performance by Duke Redbird, the legendary Indigenous poet, journalist, academic and actor, Dunn makes his glorious four-minute appearance at the festival (34:55–38:40), with the camera focusing solely on his singing and his hands playing the guitar. Amisk contains footage of so many great Indigenous artists and so much great music that it’s well worth watching every second.

Amisk, Alanis Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

October in Canada: Mi’kmaq History Month

Willie Dunn’s body of work includes 10 films made at the NFB (three as director, five as music composer, and two as cast/participant). There are indications that he also directed other NFB and non-NFB titles (e.g., The Eagle Project, The Voice of the Land and Self-Government, and possibly others[x]), and if that’s the case, I hope these films get preserved, restored and digitized and become available to the public one day soon.

Dunn’s films offer a unique Indigenous perspective on Canadian society that had not been previously seen in NFB productions. His films, and the ones made by the Indian Film Crew, laid the groundwork in terms of content for future Indigenous perspectives in NFB filmmaking, giving birth to a cutting-edge, modernizing Indigenous cinema at the Board that would continue to grow and evolve over the ensuing decades.

These Are My People…, Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell, Willie Dunn, Barbara Wilson & Roy Daniels, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

To commemorate Mi’kmaq History Month,[xi] I wanted to pay homage to Willie Dunn not only because he was a Mi’kmaq filmmaker, but because he’s one of the most accomplished artists who ever worked with the NFB. As we publish this blog post just ahead of National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, I invite you to acknowledge the enormous contribution that Indigenous artists have made to our cinema and the arts in general. For further viewing, click here to enjoy a selection of films that spotlight the Mi’kmaq and their stories, history and culture.

NOTE: This blog post was written with generous input from Coty Savard, an Indigenous producer at the NFB.

[i] The first Indigenous filmmaker in the world may be James Young Deer; see https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/sep/23/first-native-american-director

[ii] NFB film description: https://www.nfb.ca/film/ballad_of_crowfoot/

[iii] For more information on the Indian Film Crew, please see: THE NFB AND INDIGENOUS FILMMAKING THROUGH THE YEARS (circa 2008) by Gil Cardinal https://www.nfb.ca/playlists/gil-cardinal/aboriginal-voice-national-film-board/

[iv] Backgrounder written/produced by Philip Lewis and Coty Savard for Loon Lake (1968)

[v] Some files in the NFB’s archives mention that these Indigenous filmmakers participated in other NFB productions, without specifying their degree of involvement. For example, The Second Arctic Winter Games (1972) by Dennis Sawyer, who co-edited Who Were the Ones?; for more info on Sawyer’s film, please see: https://blog.nfb.ca/blog/2023/01/18/the-arctic-winter-games-promoting-olympic-and-indigenous-sports-for-more-than-50-years/

[vi] NFB film description: https://www.nfb.ca/film/other_side_of_the_ledger/

[vii] NFB film description: https://www.nfb.ca/film/who_were_the_ones/

[viii] NFB film description: https://www.nfb.ca/film/incident_at_restigouche/

[ix] NFB film description: https://www.nfb.ca/film/amisk/

[x] See these online sources:

- https://commonground.ca/native-north-america-vol-1/

- https://citizenfreak.com/artists/94463-dunn-willie;

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willie_Dunn

[xi] https://novascotia.ca/abor/office/what-we-do/public-education-and-awareness/mikmaq-history/

Header Image: The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson’s Bay Company (1972) by Martin Defalco & Willie Dunn